Land is of great significance to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples - but the connection we feel to Country can be a difficult concept for non-Indigenous people to grasp. The living environment goes beyond physical elements, and is fundamental to our identity.

For First Nations people, “Country” encompasses an interdependent relationship between an individual and their ancestral lands and seas. This reciprocal relationship between the land and people is sustained by the environment and cultural knowledge.

The land is the mother and we are of the land; we do not own the land rather the land owns us. The land is our food, our culture, our spirit and our identity Dennis Foley, a Gai-mariagal and Wiradjuri man, and Fulbright scholar.

When people talk about Country it is spoken of like a person: we speak to Country, we sing to Country, we worry about Country, and we long for Country.

To not know your Country causes a painful disconnection, the impact of which is well documented in studies relating to health, wellbeing and life outcomes... It is this knowledge that enables me to identify who I am, who my family is, who my ancestors were and what my stories are. We are indistinguishable from our country which is why we fight so hard to hang on.” Catherine Liddle, Arrente and Luritja woman, and Aboriginal activist

The interdependence between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and the land is based on respect - while the land sustains and provides for the people, people manage and sustain the land through culture and ceremony. It is because of this close connection, we see that when the land is disrespected, damaged or destroyed, there are real impacts on the wellbeing of Indigenous people.

The land is a link between all aspects of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people's existence - spirituality, culture, language, family, law and identity. Each person is entrusted with the cultural knowledge and responsibility to care for the land they identify with through kinship systems. Rather than owning land, people develop strong intimate knowledge and connection for a place that is related to them. The intimate knowledge of a place forms this strong connection that is inherent to Indigenous identity.

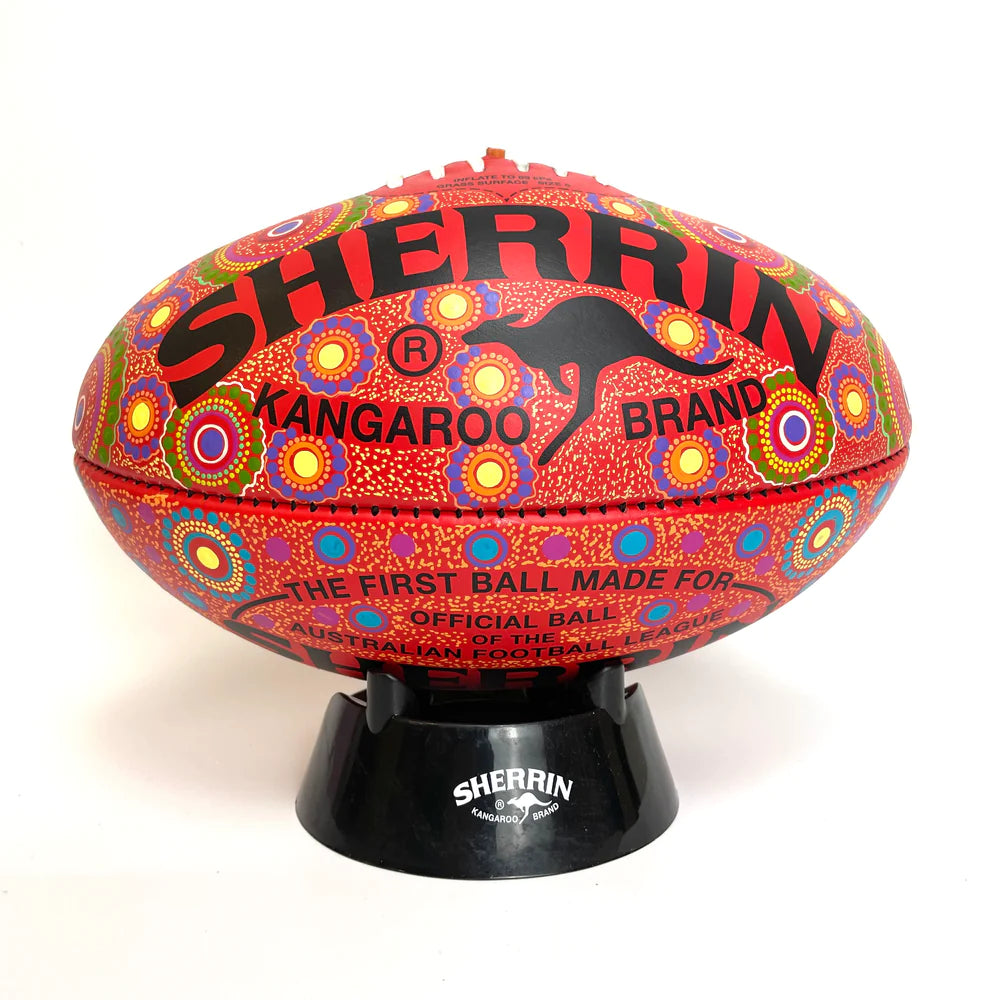

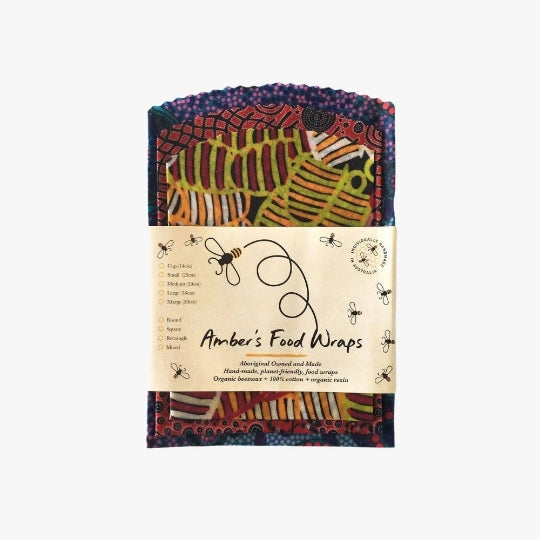

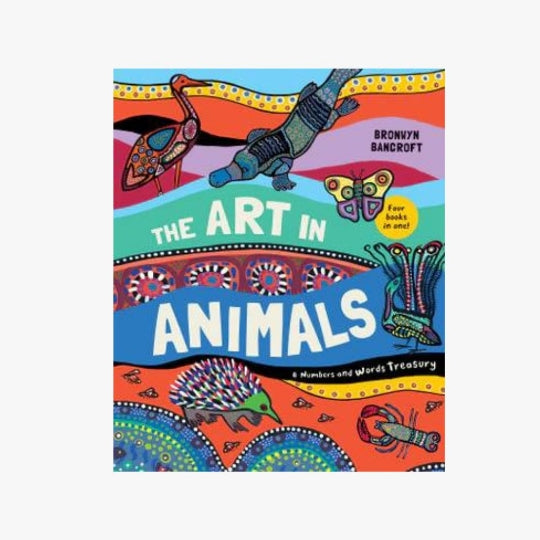

Land sustains Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander lives in every aspect - spiritually, physically, socially and culturally. The notion of landscape as a second skin is central to a lot of Aboriginal Art, whether it be theatre, dance, music or painting.

Looking After Land

“Caring for Country” means participating in interrelated activities on Aboriginal lands and seas with the objective of promoting ecological, spiritual and human health. It is also a community driven movement towards long-term social, cultural, physical and sustainable economic development in rural and remote locations, simultaneously contributing to the conservation of globally valued environmental and cultural assets [2].

The following article speaks to the impact and significance of a continuing relationship with country.

Happiness born of connectedness lifts up Aboriginal Australians

Larissa Behrendt, University of Technology Sydney

This article is part of a series, On Happiness, examining what it means and how it might be achieved in the 21st century.

I recently spent some time on an outstation in the Northern Territory. Unless you have been on one, it is hard to understand the level of poverty that some Aboriginal people live in – sleeping on concrete floors, little money, no luxuries. Life is supplemented with bush tucker and everyone works together and shares what they have.

Among the basics of life, there is resilience. But there is also something else that is perhaps even more surprising. As I sat around the campfire in the evening, what rose up into the night sky amid the smoke was laughter.

This is a community surrounded by tragedy and hard social problems. This is a community with deep concerns about the impact of mining on sacred sites, about access to education, feelings of being disenfranchised and the stresses of having very little money to survive on. In nearby towns, there are issues of substance abuse and violence. So it is easy to fall into cliché and to see this laughter as being cathartic, an important release.

But there is something deeper than just the fleeting laughter that comes at the end of a funny story, a witty comment or a parody. It always strikes me in a close-knit community that something much more profound is at work. Around a campfire with shared resources – food, clothes, blankets, utensils, even shoes – there is a deep sense of contentment, a profound happiness.

Maybe the generosity of spirit creates a deeper contentment, a deeper happiness. Or maybe it is the happiness that gives a person a more generous spirit, a larger heart.

How do you take the pain of the past, whatever your background, and make it something that doesn’t cripple you? How do you stop it from being a barrier to happiness?

Happiness knows no cultural barriers or bounds. But I wonder what can be learnt about true happiness from the Aboriginal women on the outstation who can illuminate the world of the rest of us.

Connected to community and Country

The first lesson from my friends around the campfire is the way they look at the world around them. They see its riches.

They look at the sky and understand its meanings. They look to the land and sea around them and see additional sources of food. They look at the people who make up their family and community and they see the blessings in what they do have.

They tell stories of their fishing and hunting trips, of great romances and funny anecdotes. Their world is full of rich stories, of songlines, of music, of dance. It is impossible not to be struck by the deep interconnectedness that they have with each other and with the world around them.

When you have so very little, you are reliant on the people around you. You rely on them to share resources, to help you get from one place to another (you have to share vehicles and find a way to pay for petrol), to join together to confront a school that is not working with the community or a land council that has not been negotiating properly. And through this meaningful reliance on each other – where you don’t just take but give what you have – there is deep, meaningful human connection.

This interconnectedness with other people seems to provide a strong grounding in one’s own identity, one’s own value, one’s own place in the world. This grounding is essential for a sense of self and a sense of self-worth.

How can you be happy when you are uncomfortable with who you are? How often do we see people struggle with their identity in a way that causes them distress and misery? There is none of that among people who are deeply rooted in their community and have a strong sense of their place.

There is also interconnectedness to the natural world. The women on the outstation have been hunting turtles and fishing in the waters since they were small girls. They know which plants are edible and they know what fruit is edible.

They also know the stories about the creation of the world around them, how the constellations in the sky were formed and the songlines about great trips across the country. In the world around them, there are stories and legends but there is also knowledge of the seasons and an ability to read the landscape and the weather.

Research shows that people who live on the outstations have better health than those living in town. These are alcohol-free communities but their diets are also better as a result of the richness of the food found in the land and sea, which supplements the processed, unhealthy food.

In these remote areas, fresh food is expensive. Lollies, soft drink and processed foods are cheap. Diets are poor and health is poor as a result. So on the outstations, where fruits, vegetables, fish, turtles and other bush food supplement diets, it is easy to see why people are healthier.

Lives enriched by creativity

So it is easy to see how the interconnectedness to Country is also a source of a contented life. But there is something else that engages the women here, something that is linked to their culture but also seems to be a basic element in fundamental happiness. They have a very rich creative life.

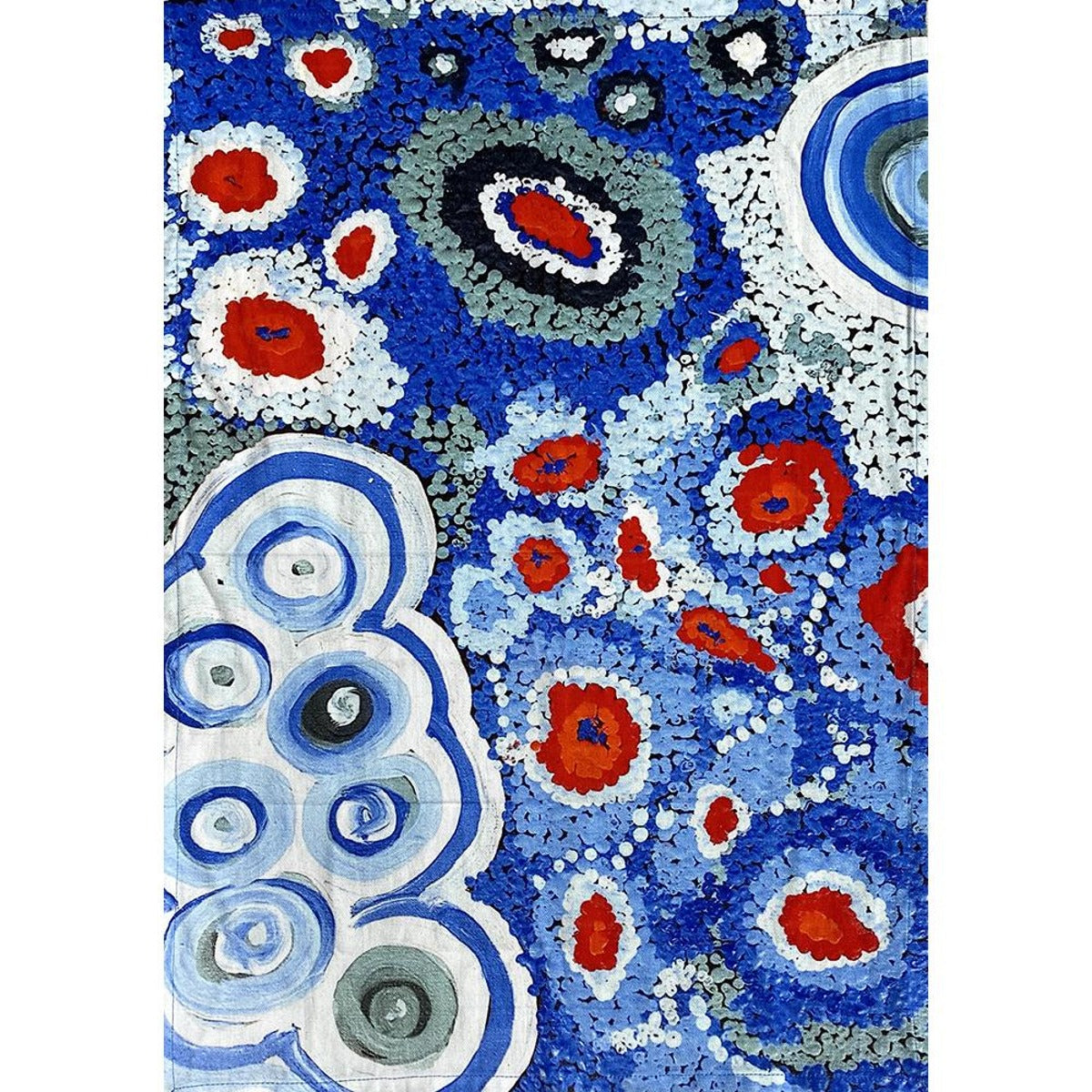

The women of this community – and some of the men – are gifted painters. They translate the stories told by their parents and grandparents into vivid canvasses. They express themselves as eloquently through their brush strokes as they do with their words.

In addition to their painting, they have their traditional songs, their songlines and their dance. They are creative performers of their cultural traditions and they not only perform but teach the children the same songs and dances.

And between the painting, the dancing and the music is a rich traditional of storytelling as old as the culture. These women are natural storytellers. Although they have not written the stories, they perform them in the way they tell them. They are the expression of the vibrancy of the world’s oldest living culture.

Living in close proximity to others is not easy and this is a community where there is overcrowding. On fine nights, people sleep under the stars, but there are not enough rooms for the number of people here and so people share concrete floors when they have to.

So life is not without its arguments and disagreements, its jealousies and bickering and all of the other things that happen between people who live closely. But the generosity and openness of the women who have the moral leadership in this community is defined by the love they have for their families, especially their children.

There is no romance in being poor, but there is happiness to be found when you can find the richness in life. That is the abiding lesson I learn from my visits to this other way of life.

And as the laughter rings around the campfire, and I listen to the women, all sisters, sing their songs, teach the children to dance, tell their ancient stories, gently tease each other – and me – it is a reminder that there are ties that are deeper than blood and that lightness of spirit is the measure of happiness.

This article is based on an essay in the collection On Happiness: New Ideas for the Twenty-First Century (UWA Publishing, June 2015).

You can read other articles in the series here.

Larissa Behrendt, Professor of Law and Director of Research, Jumbunna Indigenous House of Learning, University of Technology Sydney

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

(1) Rose D. Nourishing terrains: Australian Aboriginal views of landscape and wilderness. Canberra: Australian Heritage Commission, 1996.

(2) Morrison J, Caring for country. In: Altman J, Hinkson M, editors. Coercive reconciliation. Stabilise, normalise, exit Aboriginal Australia. Melbourne: Arena Publications Association, 2007: 249-261.

'This article has been re-published from Common Ground, a not for profit that records and shares First Nations cultures, histories and lived experiences. Learn more at www.commonground.org.au'

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.